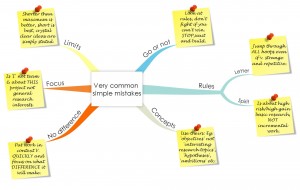

I’ll continue to work my way around the mindmap of the most common errors I have encountered when reviewing ERC proposals that I first posted in the post on ‘starting out’ . And I’ll start here by looking at the question of rules and how some researchers don’t respect them well enough to give their proposal a fighting chance of success. The common errors I have seen here break down for the sake of simplicity into those who don’t obey the ‘letter’ of the laws very well and those who don’t show well enough that they understand the ‘spirit’ of the programmes – of course, it is not uncommon to make mistakes in both respects.

. And I’ll start here by looking at the question of rules and how some researchers don’t respect them well enough to give their proposal a fighting chance of success. The common errors I have seen here break down for the sake of simplicity into those who don’t obey the ‘letter’ of the laws very well and those who don’t show well enough that they understand the ‘spirit’ of the programmes – of course, it is not uncommon to make mistakes in both respects.

Well, the rules are very easy to follow and should be followed to the letter in the order that they are set out in the guide to applicants – there is nothing complex or uncertain about this. I’d suggest that a simple way to write the B1 section, which is absolutely critical as it is the only thing that will be read in the first phase of the evaluation, is to follow the headings suggested in the Guide to Applicants for the B2 section: i.e., objectives and state-of-the-art, methods and resources. Under these general headings there are some ideas about what they are expecting to see and some guidance about what needs to be included to create a complete argument.

I always suggest using these headings as the basis for the writing of B1 as they provide a complete snapshot of the project and this is what they Guide asks you to do in B1 – give the reader enough information to be able to assess if the project is feasible. I consider that this involves a sketch of time and resources too as well as a presentation of the ideas and I think that the best strategy is to paint a complete miniature of the work – it is possible to do this in five pages quite easily if the ideas you are dealing with are crystal clear and all the text is carefully planned beforehand.

So, it might seem obvious to the reader that the rules need to be followed to the letter and in the order they are set out and that this goes without saying. However, a surprising number of proposers seem intent on re-reading the rules and proposing something to the ERC that they think is interesting or is what the ERC should be buying regardless of whether or not it is recognisably an ERC proposal that they have written.

It might not be the case that this structure is the same as the structure behind the work that the researcher has planned or developed, but it is the proposal that has to be adapted and there is no point in trying to re-interpret the rules. It might also be the case the structure is not the most logical way to present certain types of work, again, this is simply bad luck and the simple advice is the writer has no choice but to jump through all the hoops in the order they are set up – these are the rules by which the game is played. Of course, the difficult part is to create an argument using this structure and that is really the ‘art’ of the proposal writing process that I’ll try to deal with in all its aspects in later posts, but as a first step at least make sure it is complete.

Even more important than the letter of the law is the spirit of the programme which also needs to be recognised and respected – the ERC guard the unique character of their mission very carefully and it is wise to show that you take this seriously and are writing a proposal with this particular philosophy of research in mind: this helps create a powerful ‘handshake’ effect with the evaluator and is a great advantage during the evaluation procedure.

This means that the work has to appear to be customised, or ideally created especially for, the ERC programmes by showing clearly: that it is lead by an individual researcher; that it will be done at an EU institution with high levels of time dedication from that researcher; that it is not a network or a consortium action (this work can be done in other parts of H2020 and the warnings about not submitting this kind of work have recently grown stronger); that it is groundbreaking, a significant step forward given the state-of-the-art; that the benefits the work will create are both providing solutions to apparently intractable problems in the short term and opening a rich seam of possibility for more research in connected and related fields and for technology in the longer term; that it is research with some strong elements of basic research in the mix and couldn’t simply be done by a company as part of a product development cycle; that it is ‘high risk/high gain’ work etc.

What each of these ideas means in the context of these calls and the practical consequences of them for how the proposal is written will be dealt with one by one in later posts as they are key dimensions of a competitive text and each is worthy of being held up for examination and discussion separately. However, together they represent the philosophy, or ‘spirit’ of the programme which sets it apart from the rest of H2020 and other research funding on the international stage. Some aspects of the approach are easy to object to perhaps – the emphasis on ‘heroic’ pioneering individuals might not be in tune with some visions of how science is in fact done – and some elements are tricky to do – how do you speak about breakthroughs, which is to speak about the new, from the position of current and past knowledge (it demands a certain Janus-faced writing style which is not easy to balance) – but, in the end, this is the game, these are the rules and those who control them the best will get closest to winning.